cost of capital africa:

High borrowing costs mean that African governments often must choose between making debt payments and investing in health. This November’s G20 summit – the first to be held in Africa, and the second with the African Union as a permanent member – represents a critical opportunity to create better options.

May’s 78th World Health Assembly (WHA) – the annual meeting of the World Health Organization’s member states – ended on a self-congratulatory note. From an agreement on pandemic preparedness to increases in assessed contributions to the WHO, there were plenty of achievements to tout. But there was an elephant in the room, hiding behind a banner reading “One World for Health” (the event’s theme): the high borrowing costs faced by African countries.

Despite being the world’s youngest continent, Africa bears 24% of the global disease burden. Yet it accounts for less than 1% of global health spending. In 2001, African countries decided to take matters into their own hands, pledging to devote at least 15% of national budgets to health. Yet, more than two decades later, only twocountries have reached that target. On average, governments on the continent allocate a mere 1.48% of their GDP to health, while 37% of health spending comes directly out of citizens’ pockets.

Borrowing costs are a major reason why. Whereas high-income countries borrow at an interest rate of 2-3%, their African counterparts can face rates above 10%. This discrepancy – which reflects investors’ perception of heightened risk in African economies – means that governments on the continent often must choose between making debt payments or buying medicines, hiring doctors, and building health clinics. The cost of capital costs lives.

Consider Kenya’s ill-fated Managed Equipment Services (MES) program, a public-private partnership aimed at enhancing service availability at hospitals through the provision of modern equipment. The program did provide high-tech equipment to many hospitals. But, given the cost of capital for investment, Kenya could not deliver the infrastructure or personnel to use it.

In Ghana, where debt-service costs have left little fiscal space, nearly 75% of the government’s health budget now goes to health-care workers’ wages, leaving little funding for other crucial expenses, from medicines to maternal-health programs. In 2023, a shortage of antimalarial drugs forced some rural clinics to direct patients to purchase the medicine they needed directly from private pharmacies. Many families thus faced a harrowing choice between being driven further into poverty and sending a loved one to an early grave.

For many African countries, high borrowing costs have contributed to dependence on the goodwill of foreign donors. But aid-dependent health-care systems are fundamentally fragile. We saw this during the COVID-19 pandemic, and we are seeing it now, as European countries scale back their development spending to free up space for other priorities, and the United States dismantles its entire aid apparatus, beginning with the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

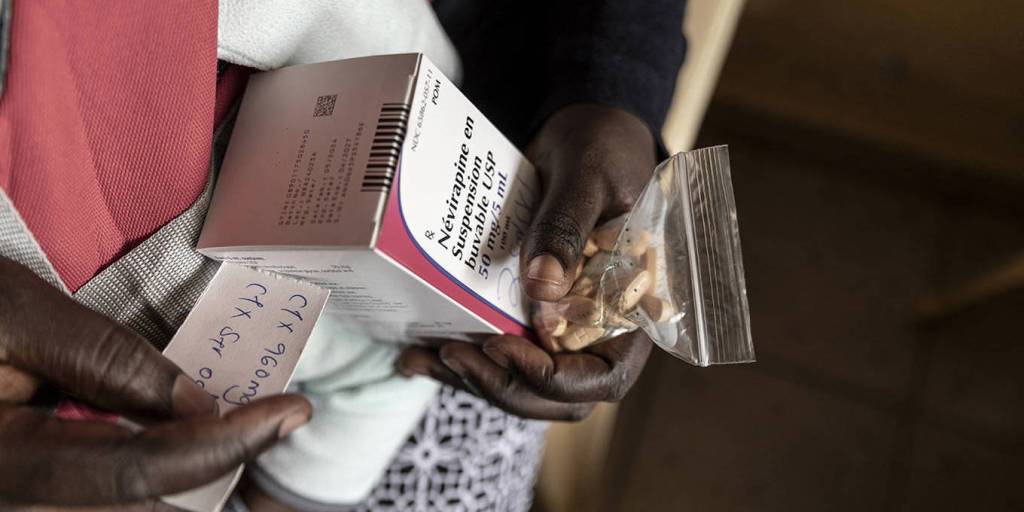

In Malawi, those cuts have already forced critical programs, such as for HIV treatment and prevention, to scramble for funds. Local NGOs have been forced to lay off outreach workers, and patients with tuberculosis or HIV have gone without care. As one community health nurse in South Africa lamented, “My fear is mortality is going to be very high.”

Africans’ health cannot depend on the generosity of others. Governments must be able to invest in stable, resilient, self-sustaining health systems. To raise funds, Senegal and Zambia are experimenting with “health taxes” on alcohol and sugary drinks. Debt-for-health swaps in countries like Seychelles have shown promise. Nigeria’s diaspora health bonds could unlock billions in financing if they are matched with concessional capital and guarantees from multilateral banks.

Ultimately, there is no substitute for affordable, predictable capital. That is why lowering borrowing costs must be a key priority at the G20 summit this November.

This means, first, tackling structural factors such as outdated international regulations and biases in risk assessments. It also means delivering timely and meaningful debt relief. This will require innovative mechanisms, such as debt-for-health swaps, and increasing the use of pause clauses in existing loans and new debt contracts that allow for debt payment suspension when a pandemic strikes.

A third priority must be to secure continued political support for multilateral health programs – such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria – thereby ensuring continuity in the delivery of the relevant health services. Finally, the G20 must seek to expand African countries’ access to concessional financing for health infrastructure through multilateral development banks.

The G20 is the right forum for these actions. Its mandate includes addressing global challenges, promoting economic cooperation, and fostering global stability. The cost of capital is beyond any one country’s capacity to address, and it is producing a destabilizing global-health emergency. The upcoming G20 summit, the first to be held in Africa – and the second with the African Union as a permanent member – represents a particularly fitting moment for such action.

Within African countries, mechanisms – based on civil-society engagement – for ensuring accountability for how funds are spent are also essential. But the first step must be to free up the funds. To achieve “One World for Health,” all countries must be able to access the means to invest in health care.

Serah Makka is the Africa Executive Director at The ONE Campaign, while Rosemary Mburu is Executive Director of WACI Health. This op-ed article was originally published in Project Syndicate, African Newspage’s publishing partner. The views it expresses do not necessarily reflect African Newspage’s editorial policy.

The post OP-ED | The Cost of Capital Is a Public-Health Emergency for Africa, By Serah Makka & Rosemary Mburu appeared first on African Newspage | Reporting Africa’s Development.

cost of capital africa and Its Impact on Healthcare Infrastructure

The high cost of capital africa directly affects the development and maintenance of healthcare infrastructure across the continent. Hospitals and clinics often struggle to secure affordable financing for building new facilities or upgrading existing ones, which delays critical improvements in patient care. For example, in Kenya, programs intended to modernize hospital equipment face severe budget constraints due to borrowing costs, limiting their effectiveness despite ambitious goals. Without accessible capital, health systems remain fragile and unable to meet growing demand.

This financial strain contributes to uneven access to quality healthcare services between urban and rural areas. While cities might attract private investment, rural clinics frequently suffer from shortages of medicines and staff. International organizations and governments have recognized the urgency of the problem. Innovative financing models like debt-for-health swaps and “health taxes” on products harmful to wellbeing have been piloted in several countries, with varying success. For more insights on political and economic factors affecting Africa’s health, visit Voice Mauritius News – African Political Shifts 2025.

Meanwhile, international financial institutions like the World Bank and African Development Bank are urged to offer more concessional loans targeted at health infrastructure projects. By reducing interest rates and extending repayment terms, these banks can help bridge the funding gap. Ultimately, tackling the cost of capital africa is essential for building resilient health systems capable of serving all populations equitably.

cost of capital africa: Challenges in Securing Affordable Funding

Securing affordable funding remains one of the most significant challenges facing African governments due to the cost of capital africa. Investors often perceive higher risks in African economies, leading to interest rates that can exceed 10%. This discourages borrowing for critical sectors such as health, as governments must weigh debt repayments against essential expenditures like medicines and staff salaries. The consequences of these financial dilemmas are stark: shortages of life-saving drugs, underpaid healthcare workers, and delayed public health initiatives.

Take Ghana’s health sector as an example, where nearly 75% of the health budget is consumed by salaries, leaving minimal funds for medicines or maternal health programs. The ripple effect of these constraints forces vulnerable populations to make difficult choices between healthcare and basic needs. External aid has historically provided temporary relief but is no substitute for sustainable financing. As donor countries shift priorities, African nations face increasing pressure to find innovative financing solutions. A recent analysis by African Newspage highlights how strategic reforms could reduce borrowing costs and improve health outcomes.

Efforts to introduce “health taxes” on sugary drinks and alcohol or to issue diaspora health bonds show promise but require political will and robust governance. Multilateral development banks can play a pivotal role by increasing concessional lending and supporting debt restructuring initiatives. Addressing these financial challenges is critical for Africa to escape the cycle of debt and underinvestment in health.

cost of capital africa and the Role of Global Partnerships

Global partnerships are vital in addressing the cost of capital africa and its public health implications. The upcoming G20 summit, hosted in Africa for the first time, presents a unique platform to advocate for lower borrowing costs and more flexible financial arrangements. Multilateral institutions such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria depend on sustained political and financial support to continue delivering essential services. Without affordable capital, these programs risk losing effectiveness and reach.

At the national level, countries like Senegal and Zambia are experimenting with innovative solutions such as debt-for-health swaps, which convert debt repayments into investments in health infrastructure. Nigeria’s diaspora health bonds could unlock significant capital if paired with concessional loans and guarantees from international banks. These examples underscore the potential for creative financial instruments to bridge funding gaps. However, the success of such measures depends heavily on accountability mechanisms to ensure funds are properly managed and utilized.

Ensuring transparency and civil society engagement in monitoring expenditures can strengthen trust and improve outcomes. The role of the G20 in facilitating cooperation and addressing structural barriers in international finance cannot be overstated. By reducing the cost of capital africa, the global community can help build resilient health systems that serve millions and prevent future crises.

cost of capital africa: The Path Forward

Addressing the cost of capital africa requires urgent collaboration between African governments, multilateral institutions, and international partners. Innovative financing mechanisms, debt relief, and concessional loans are vital tools in this effort. Empowering local civil society to ensure accountability will further strengthen investments in health. The upcoming G20 summit offers a pivotal opportunity to make significant progress in lowering the cost of capital africa and improving health outcomes continent-wide.

Conclusion: cost of capital africa

The cost of capital africa remains a critical barrier to building sustainable and effective healthcare systems across the continent. Without addressing the cost of capital africa, African governments will continue to face impossible choices between servicing debt and investing in essential health services. It is imperative that global leaders prioritize reducing the cost of capital africa to unlock the funding necessary for resilient health infrastructure and equitable care. Only through coordinated international efforts and innovative financial solutions can Africa overcome this public health emergency and secure a healthier future for all its citizens.

Source: African Newspage Official Website